|

History

For centuries, philosophers and other scholars have argued over

the nature of the mind and how it functions-the phenomena of mental

life. But the relatively recent idea of using scientific methods

to resolve such issues was what distinguished modern psychology.

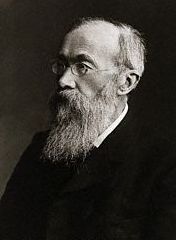

In 1879 Wilhelm Wundt, a professor at the University of Leipzig

in Germany, opened the first laboratory devoted exclusively to the

study of psychology. Experiments were carried out under carefully

controlled conditions to answer basic questions about the human

mind.

Because most of the important first-generation psychologists studied

under Wundt, the new discipline began as a basic science concerned

mainly with laws of conscious experience. However, Hugo

Munsterberg and Walter

Dill Scott, two of Wundt's students who established themselves

in the United States, began to explore the applications of psychological

principles to industrial problems. Both wrote important books on

these applications. Munsterberg was concerned primarily with industrial

efficiency and Scott's (1908) with advertising. Between them they

touched on many of the topics that have occupied I/O psychologists

ever since.

At about the same time that Wundt was trying to describe the general

laws that govern mental life, a British scholar and cousin of Charles

Darwin, Sir

Francis Galton, was studying how people differ from one another

mentally. Coupled with the work of Alfred Binet, the pioneer in

intelligence testing who gave us the concept of IQ (intelligence

quotient), Galton's approach spawned a tradition in psychology that

developed largely in parallel with Wundt's mental science (Hothersall,

1984). It has often been called the "mental testing movement".

Testing for individual differences and doing experiments to discover

general mental principles have remained fairly distinct approaches

in psychology despite periodic efforts to draw them together (Cronbach,

1957). Wundt's mental science approach dominated early psychology

in the United States, but the practical possibilities of testing

are what captured industry's interest. Hence, the individual differences

approach became dominant in early industrial psychology and remained

so for the next several decades.

During this period, Sigmund Freud's theories on the nature and

treatment of mental disorders (and the role of unconscious events

in mind and behavior) were also beginning to attract a great deal

of attention, eventually helping to establish the health-care branch

of psychology (Hothershell, 1984). Still, until nearly midcentury,

psychology remained chiefly an academic discipline rooted in laboratory

research. The industrial and clinical branches were considered peripheral,

trivial and rather suspect offshoots, often lumped together as "applied

psychology".

The evolution of I/O psychology from a minor offshoot to a recognized

specialty within the field can be traced to a number of influences,

but none more important than the two world wars. The demands of

two massive war efforts, each representing dramatic changes in the

doctrine and technology of warfare, called for radical changes in

the management of human resources. Psychologists of all kinds were

summoned to help, and in the course of doing so they discovered

a great deal about the potential applications of their specialized

knowledge and techniques. All branches of psychology made huge advances

under the exigencies of war-an ironic twist of fate for a discipline

pledged to the promotion of human welfare.

Both wars provided massive evidence of the value of testing for

selection and assignment of people according to job requirements.

Naturally, industry recognized the potential applications of these

techniques, and the use of testing increased dramatically after

both wars. In addition, World War II produced important advances

in techniques used to train people, many of which found peacetime

application. Educational, experimental, and industrial psychologists

all contributed significantly to the design of these training programs.

One notable example was simulation training, a technique in which

the basic operations required in a job could be practiced on a replica

of the job's environment without the risks and costs associated

with learning in the actual situation.

In addition to selection, classification, and training developments,

WWII fostered the creation of a whole new field based upon an entirely

different strategy for improving human effectiveness. The essential

idea behind it was that "human error" or poor performance

is not always a matter of incapable or poorly trained personnel,

but often reflects insufficient consideration of human characteristics

in the design of the machines that people must operate. The field

survived the war, and today constitutes a formally recognized as

ergonomics.

In the three decades following WWII, all areas of professional

psychology experienced tremendous growth, and the industrial field

was transformed from a narrow applied specialty with a distinct

emphasis on personnel functions to the multifaceted discipline that

it is today. The official name was changed from industrial to industrial/organizational

psychology in 1973 to reflect the growing influence of social psychology

and other organizationally relevant social sciences.

One final trend in psychology has shaped the I/O field. Since the

early 1900s, psychology has tended to be dominated by one or another

theoretical perspective or kind of explanation (often called a "paradigm")

during any given era. Early on, as we saw, the emphasis was on describing

the general laws that govern conscious experience. Using introspection

as a research tool, psychologists such as Wundt attempted to analyze

and describe the contents of conscious experience (e.g. sensations,

images, feelings) similar to the way a chemists might analyze the

elements of matter. This paradigm was often referred to as structuralism

because of its focus on the structure of mental content. Freud's

work on the unconscious, however, coupled with a growing realization

that much of what happens concsiously occurs for a purpose, shifted

attention to the more dynamic functional properties of mind. From

the late 1920s until the 1940s, therefore, the emphasis was on the

mental and biological underpinnings of functions such as motivation,

emotion, learning, and perception. The primary concern of functionalists

was how humans and other living organisms adjust to their environment.

This school of thought, which constituted America's first unique

paradigm, became known as American functionalism (Hothersall, 1984).

It was a much less restrictive school of thought than structuralism,

a feature that enabled both the individual differences approach

and applied psychology to develop within it. William

James, a Harvard professor who has often been called America's

most influential psychologist and interestingly was the one who

brought Hugo Munsternberg to the US.

Functionalism gave way to another paradigm, behaviorism, under

the leadership first of John B. Watson, and later B.F. Skinner (Hottersall,

1984). Behaviorism held that both the content and functions of the

mind are unsuitable subjects for scientific study because neither

is open to public view. All that can be studied objectively are

the behaviors (responses) that organisms exhibit and the environmental

conditions (stimuli) that control them. In its most radical form,

behaviorism denied the very existence of mind and maintained that

all behavior could eventually be explained in terms of simple stimulus-response

(S-R) laws.

From an applications standpoint, behaviorism focused on ways to

shape or control behavior by manipulating stimulus conditions and

consequences of behavior. Behavior modification ("B-mod")

techniques became popular in clinical, counseling, developmental,

school and even I/O applications, and in various forms remain so

today. However, as a general philosophy, behaviorism never dominated

the I/O specialty as it did the broader field of psychology during

the 1950s and 1960s. That undoubtedly was attributable to I/O psychology's

lack of any theoretical orientation during much of this period and

its heritage in measurement and individual differences.

By the 1970s, the study of mental events, which behaviorism had

all but eliminated from psychology began making a dramatic comeback

thanks largely to the evolution of the computer. Here at last was

a convenient model for how the human mind might work. To function

effectively, the mind must perform many of the same operations as

a computer, such as sensing and interpreting input information,

storing it in various ways, performing logic tests, and selecting

response. Mental functions could be inferred by analogy and cast

into the form of hypotheses that could be tested rigorously in the

laboratory.

The latest paradigm shift is still in full swing. It emphasizes

cognitive processes (thinking) and has touched virtually every corner

of modern psychology, form clinical practice to the basic science

of conscious experience-Wundt's domain.

|

|